News

.png)

Where to catch the investment waves in 2026

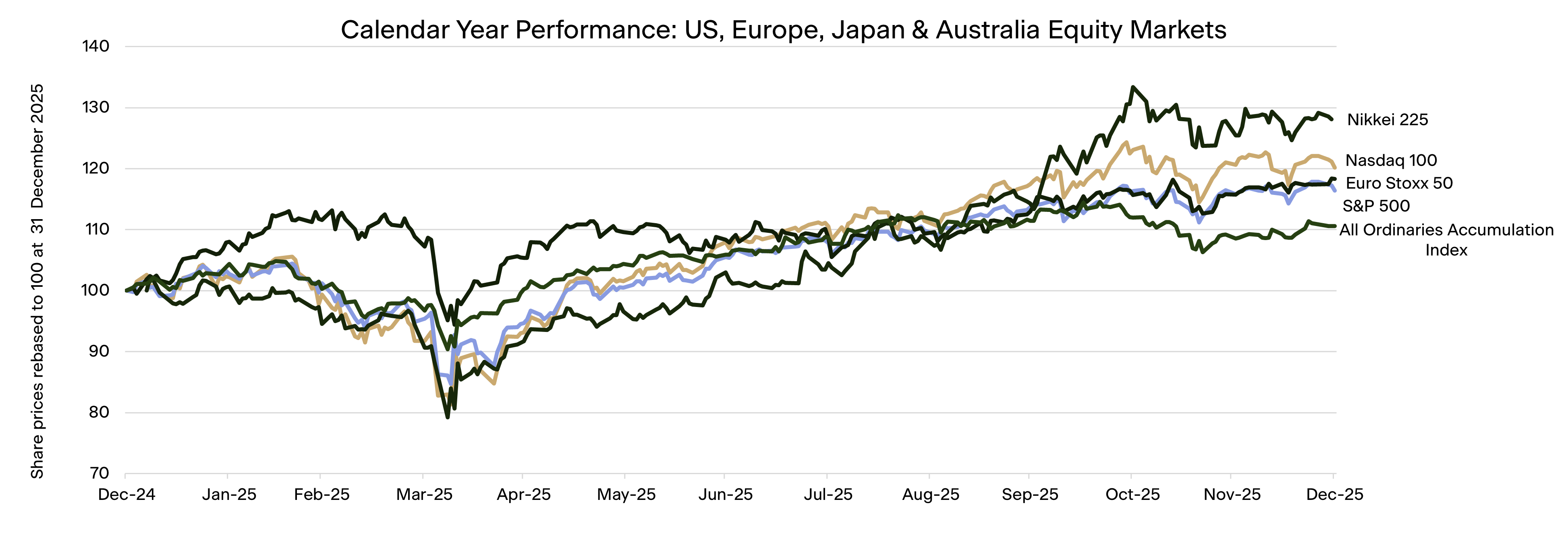

If you look only at the headline index numbers this year, 2025 looks fairly straightforward. The All Ordinaries Accumulation index returned just over 10% for the year and the MSCI World Index approximately 20%, putting both modestly above long-term equity returns of 7-8% per annum. On the surface it looks like a decent, if unspectacular, year. Under the surface, it was far more eventful.

The Australian market was one of the worst performers globally. While the tech-heavy Nasdaq Index (+20%) outperformed the broader S&P 500 (+16%) for the year on the back of big tech and Artificial Intelligence (AI) enthusiasm, it was a strong year for European markets too, particularly those in the south. Italy’s FTSE MIB rose 32%, Spain’s IBEX 35 added 49% and Greece’s ASE Index a whopping 44%.

Source : Bloomberg

Even within markets, dispersion has been the defining feature of the year. The gap between winners and losers has been wide. Abnormally, that has almost been as true at the larger end of the market as the smaller end. Here in Australia, investors in the likes of CSL (ASX:CSL),CBA (ASX:CBA) and James Hardie (ASX:JHX) learned that size doesn’t protect you from things going wrong. In fact, for the first time in a long time, the Small Ordinaries’ almost 25% return trounced the All Ordinaries for the year, with mining stocks, especially gold-related, posting a bumper calendar year (the ASX Small Ordinaries Resources Index was up 70%). Even in the Nasdaq 100, 20 stocks fell more than 10% in 2025.

Dispersion has always been a feature of financial markets. If it didn’t exist, we wouldn’t have a job. As much as balance sheet analysis and stock valuation matter to Forager’s process, a huge component of our excess returns involves finding unpopular stocks that can one day be popular again. Benjamin Graham quoted Horace almost 100 years ago in his seminal value-investing book Security Analysis and the philosophy is relatively unchanged:

“Many shall be restored that now are fallen, and many shall fall that are now in honour.”

What has changed is that the waves of popularity seem more extreme than ever. We’ve written a lot this year about the structural influences increasing the momentum-driven nature of stock markets. Want to bet on European defence stocks? Here’s the Betashares Global Defence ETF for you (ticker ARMR), available via any Australian broker and up a miserly 44% in 2025.

While it can be painful to miss these waves and even worse to get dumped by one, the opportunities for the patient long-term investor are excellent. The unloved can be a source of great ideas, and the payoff even better than expected if the sentiment changes for the better.

Some nice waves in 2025

With concentrated portfolios and small-cap stocks, there will always be a strong idiosyncratic element to Forager’s returns. The most significant contributor to the Forager International Fund’s 15% return in 2025 was US hospital owner Nutex Health (NASDAQ:NUTX). Its share price rose 420% for the year despite the healthcare sector as a whole struggling. Cuscal (ASX:CCL) was the second biggest contributor to the Australian Fund’s returns despite the payments sector globally having a very difficult year.

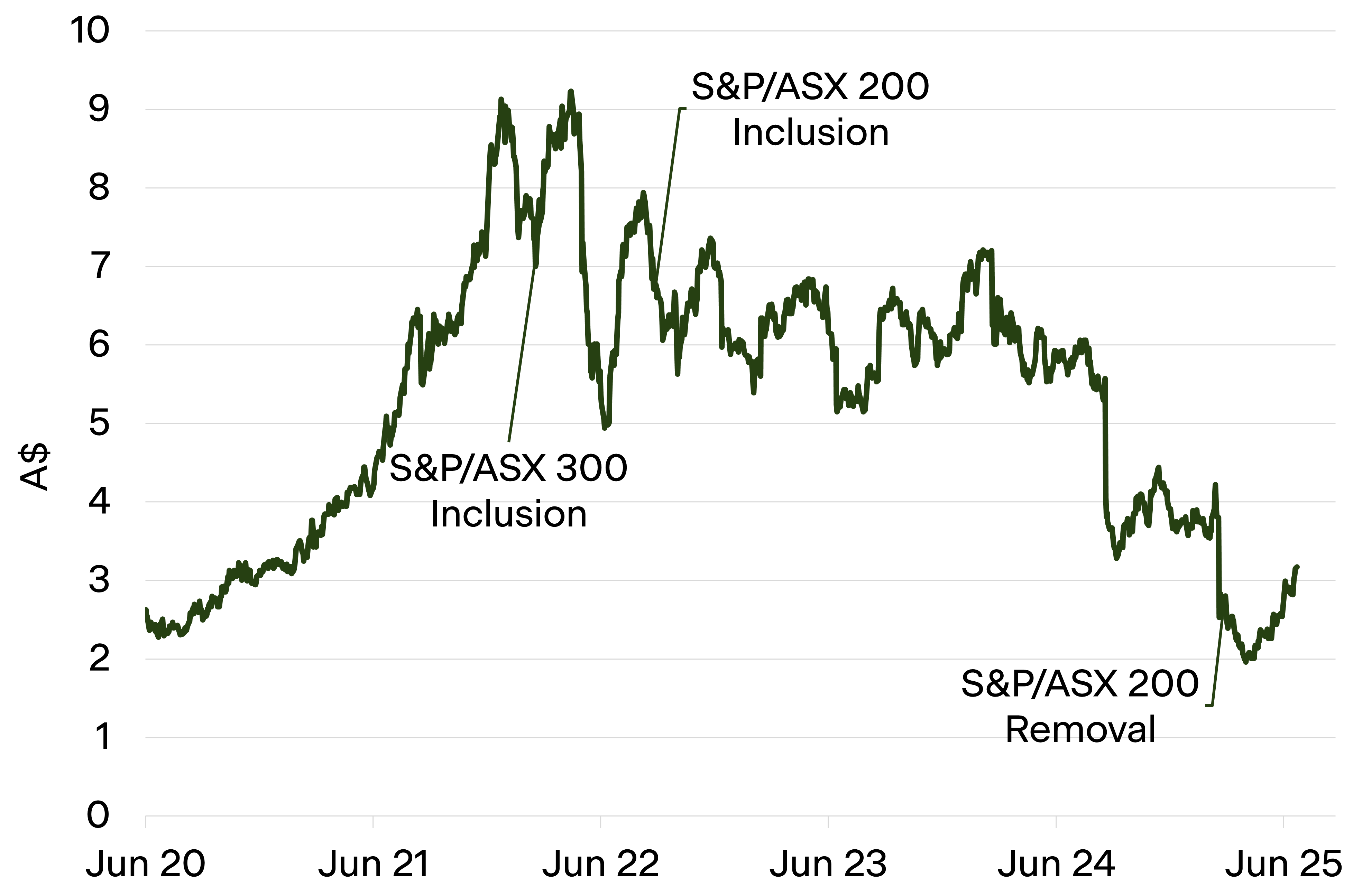

But we also managed to catch a few of those big waves that defined the year on stock markets. AI companies’ insatiable demand for data centres and power generation led to 120% and 139%respective returns for heating and cooling system installer Comfort Systems (NYSE:FIX)and solar equipment company Nextpower (NASDAQ:NXT) in the International Fund. And a widespread tech rally in the first nine months of the year led to sensational gains for our once-cheap collection of ASX-listed tech stocks like Bravura (ASX:BVS) and Catapult (ASX:CAT). Both of those companies were added to S&P/ASX indices, boosting their returns, and Comfort Systems and CRH were added to the S&P 500.

The net result was very healthy gains for both funds despite large parts of the market (and our portfolios) not “working”.

Past performance is not indicative of future performance and the value of your investments can rise or fall. Performance returns are calculated using exit prices, net of all fees and expenses and assume distributions have been reinvested.

Where to catch a wave in 2026

Looking into the year ahead, the first place to consider is always your local surf break. In 2025, some of our favourite investing sectors became too popular and crowded. As outlined in the September Quarterly Report, we banked profits on the likes of Catapult and Bravura, but they, and many of their peers, are well entrenched on the watchlist. The subsequent three months saw a significant pullback across the whole ASX-listed tech sector. Catapult’s share price fell 40% for the final quarter of 2025 and Bravura was down 27% from its recent high on 10 October. Even market darling Xero (XRO) fell 41% from its highs in June.

Some of them are perceived to be AI losers. The value of software, in a world where anyone can use AI to “vibe code” their way to a new website or app, is significantly diminished. That’s the theory.

It is a theory we are willing to bet against at the right price. Forager is a user of Xero’s product and won’t be vibe coding our accounting software any time soon. Even if we could build an accounting system, software isn’t just about features. Security, backups and constant improvements are at least as important. There is no chance of us taking a risk on any of those in order to save a few thousand dollars a year.

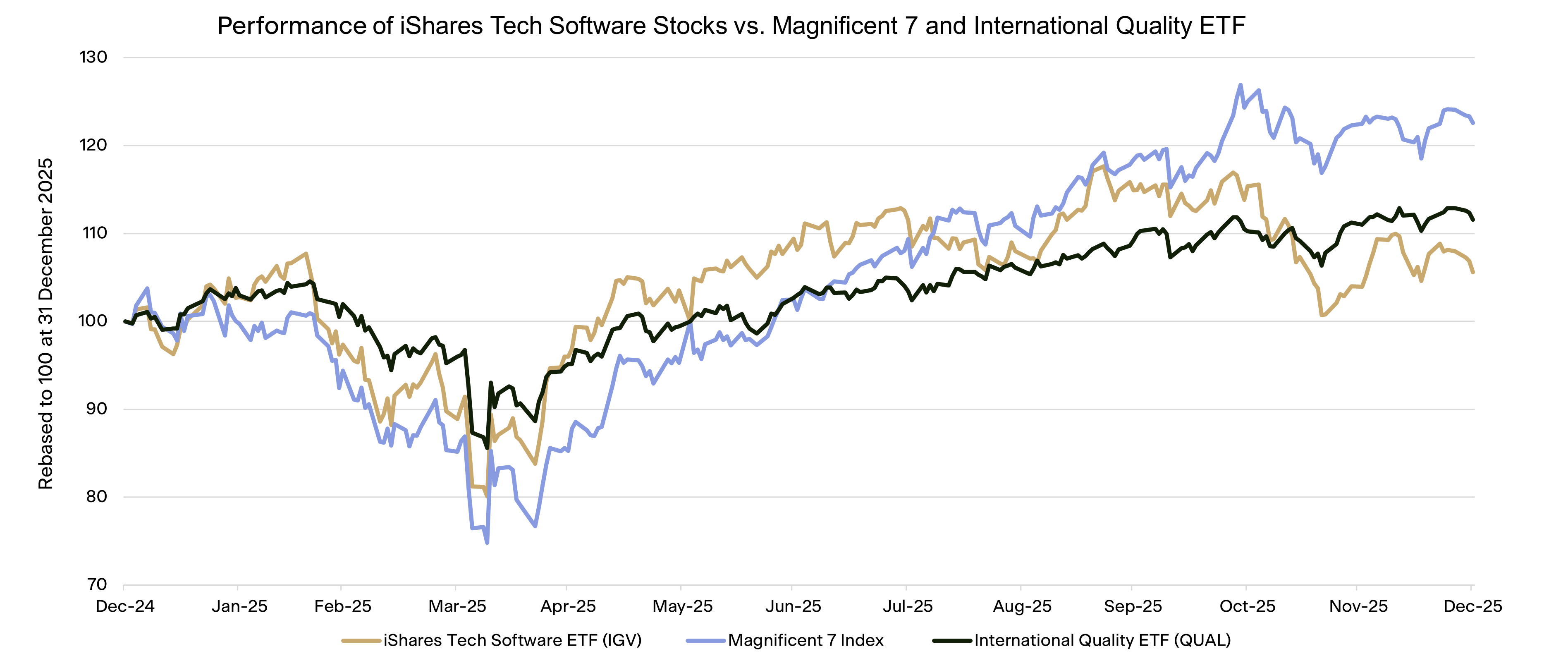

Source : Bloomberg

Many of these stocks had become expensive. Despite the recent falls, the share prices of most are still up meaningfully for the year and still aren’t cheap enough (including Xero). We haven’t deployed much capital into the Australian stocks yet, but are a lot closer than we were just three months ago. In the International Fund, we have added three technology companies that have each halved and worse over the course of 2025 and hope to add a few more. All three can be substantially higher portfolio weights should we get some thesis-confirming evidence over the next few quarters.

“Quality” has its year in the shade

Who wouldn’t want to buy a business with a strong moat, decades of earnings growth behind it and a great management team? Not only does investing in these “quality” businesses sell well, it has worked well for most of the past 15 years. In 2025, it didn’t. Australian investors in favourites like Carsales (ASX:CAR), Resmed (ASX:RMD), Cochlear (ASX:COH) and CSL suffered the same fate as investors in global equivalents like UK property website Rightmove (LON:RMV)and global insulin and weight loss giant Novo Nordisk (CPH:NOVO-B).

Share prices had been growing faster than earnings for many of these companies and the past year showed that the resultant high multiples can be a problem, even for the best of businesses. The result can be years of no returns while the earnings catch up to the share price. Or a significant derating if the earnings and the multiple come into question. Both Novo Nordisk and CSL suffered the latter fate in 2025. So did Fiserv (NASDAQ:FISV), a long-held investment in our International Fund.

We, too, like these quality attributes when we can buy them for an appropriate price. For Forager, they are inputs into our valuations, rather than a standalone investing strategy. We can and do buy lower quality businesses and invest in riskier situations, managing the risks with portfolio management. That flexibility has been helpful this year—some of our lower quality businesses have generated excellent returns—and the flexibility might also help find some quality opportunities at attractive prices in 2026.

Australian tourism finally recovers?

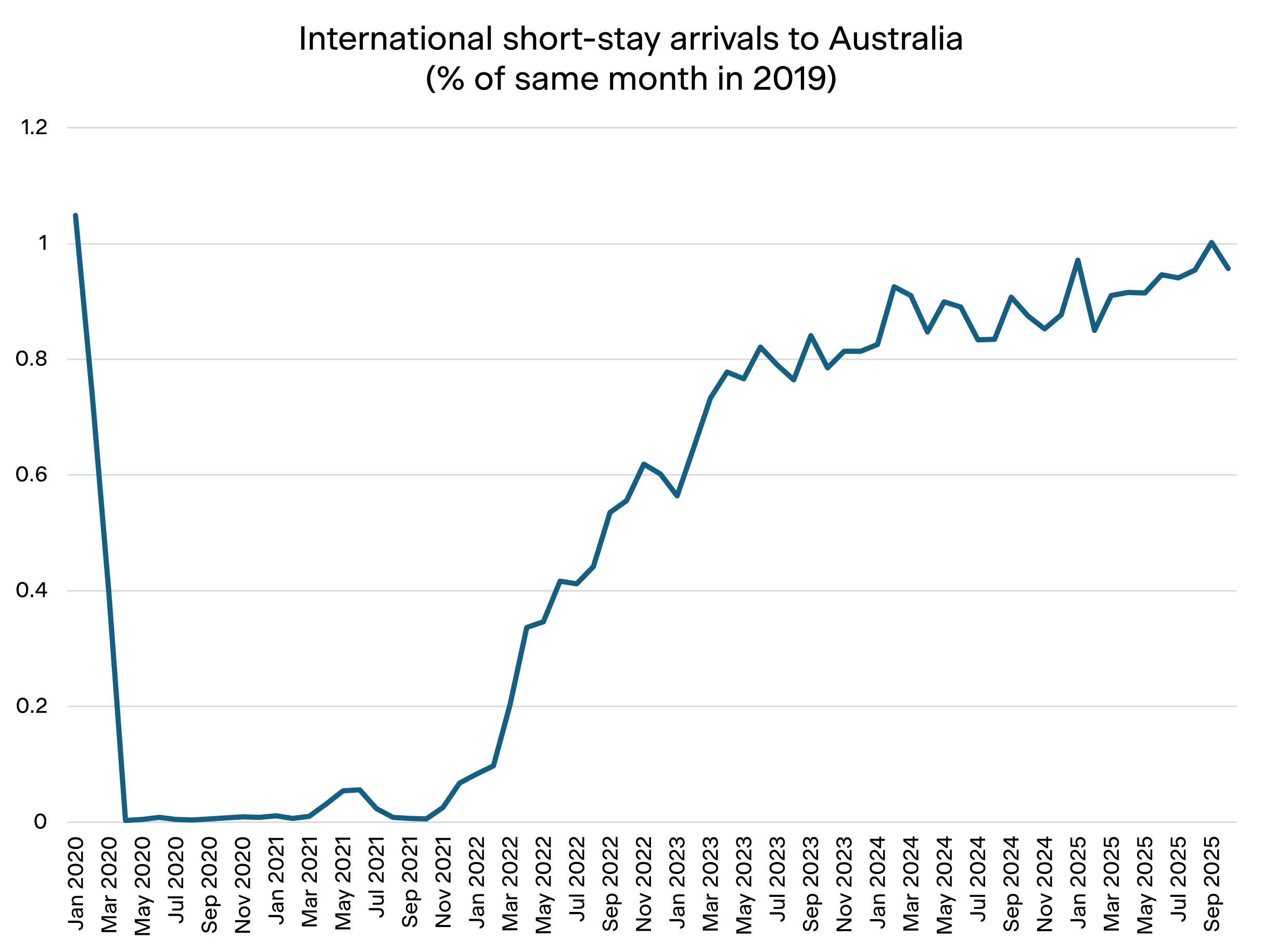

We’ve been paddling around this beach for four years now, were dumped twice and haven’t caught a wave. But could 2026 be the year Australian tourism finally gets some momentum?

Source: Australian Bureau of Statistics, Overseas Arrivals and Departures, Australia October 2025

There are not many great businesses in the tourism sector. There are exceptions, like global travel booking platform Booking Holdings (NASDAQ:BKNG) and scaled, asset-light hotel operators like Accor (EPA:AC) , but the industry is generally characterised by low barriers to entry and wild swings in demand. Stock prices for our two ASX-listed tourism companies, Experience Co (ASX:EXP) and Tourism Holdings (ASX:THL), remain near 2022 levels.

Yet the environment continues to improve. International arrivals into Australia set post-Covid records in the past three months. Relative to 2019, August, September and October combined saw arrivals hit 97% of the equivalent period in the year prior to Covid. It’s been a longtime coming, but there is no reason the growth should stop there. Travel has historically grown at a multiple of GDP growth and there is still some catching up to do.

Those two stocks are very cheap on anything like recovered earnings. And we have recently added a Spanish hotel booking platform company to the International Fund. Its earnings have already recovered, but it trades at a multiple of just six times those earnings.

Given the amount of suffering in the sector over the past decade, it’s hard to see others getting too excited. Less pessimism would help, though. And who knows? Our mining services investments spent a decade in the wilderness before doubling and more over the past 12months (in Perenti’s (ASX:PRN) case, mostly after we sold it). A travel ETF anyone? ASX code FUN, of course.

An environment that should only get better

Forager will likely get off waves far too early. We may well stay on a few too long. We are going to suffer periods where we miss them altogether and others where we paddle around waiting for a wave for years longer than we initially might expect. But the swells creating good investing conditions aren’t going anywhere. Active equity strategies saw record outflows again in 2025. The running total globally is US$3 trillion out of active and US$6 trillion into passive strategies since 2015*. It has been another year where we saw multiple active managers liquidate their portfolios and shut up shop in Australia. For those of us fortunate enough to have loyal long-term clients and some good results on the board, that’s all a source of opportunity that’s hard to see going away.

*latest data from at https://www.ici.org/research/stats/combined_active_index

This is an excerpt from the upcoming December 2025 quarterly report. If you would like to receive the report to your inbox, please subscribe to our investing community:

The Business of Booze: Can Zero be Diageo's comeback story?

The Business of Booze: Can Zero be Diageo's comeback story?

The global alcohol industry has long been considered a steady, defensive corner of the market. But in the latest episode of Stocks Neat, hosts Steve Johnson and Gareth Brown unpack why that assumption has been badly tested in recent years, and what, if anything, might revive the sector.

Drawing on Gareth’s recent trip to London and conversations with global drinks giant Diageo (LON:DGE), the episode explores falling consumption and generational change. Plus the surprising role alcohol-free beer could play in reshaping the industry’s economics.

A sector nursing a hangover

Once prized for its reliability, alcohol has become a difficult place for investors. Diageo’s share price, for example, has more than halved from its 2022 peak. As Gareth explains, Covid accelerated demand for alcohol, but global sales volumes have been falling each year since.

World alcohol volumes have been flat to falling since 2022, with younger generations drinking less, or not at all.“There is a significantly higher percentage of that 18 to 35 bracket that abstain from alcohol,” Gareth notes, as health consciousness and cost of living pressures reshape how younger people socialise. Add to that the rise of substitutes like legalized cannabis in parts of the US, which has particularly hit beer consumption, and it’s clear why markets have soured on what was once seen as a “cash machine” industry.

Premiumisation, pressure, and profitability

Gareth’s argument is that beer used to deliver better returns because it can be made quickly, so breweries can reuse the same production assets and working capital more often. But the rise of craft beer and easier access to distribution has increased competition and pricing pressure, which has eaten into beer’s old advantage.

Furthermore as Steve puts it, the old moat of mass advertising and sponsorships is largely gone. Today, celebrity-backed spirits and boutique brewers can reach consumers directly, forcing incumbents into a costly game of catch-up.

The Guinness Zero surprise

One of the most intriguing insights from Gareth’s London trip is the resurgence of Guinness, powered in part by Guinness Zero. In UK pubs, Guinness now appears to dominate taps, and alcohol-free Guinness reportedly accounts for a significant share of sales.

During the episode, Steve and Gareth even conduct a blind taste test between regular Guinness and Guinness Zero. The result? Both could tell the difference, but only just.

“It’s easier to make a complex zero-alcohol beer than a simple one,” Gareth explains, suggesting why brands like Guinness may have an edge as consumers cut back without fully opting out. Crucially, Guinness Zero sells at similar prices to its alcoholic counterpart, without excise taxes, creating potentially attractive economics for producers.

Key moments in the episode

- [00:39] Why Stocks Neat is tackling the “business of booze” now

- [03:17] Gareth on meeting Diageo and why big incumbents still matter

- [05:26] Global alcohol consumption trends—and why volumes may never recover

- [08:13] Younger generations, abstinence, and the cost-of-living squeeze

- [12:23] Cannabis as a substitute: why beer has been hit hardest

- [15:55] Beer vs wine economics and lessons from past industry mistakes

- [21:55] Guinness, alcohol-free beer, and a blind taste test surprise

Watching, not rushing

The episode ends on a cautious note. While the sector still generates enormous cash, its future depends on how younger consumers behave if economic pressures ease and whether management teams resist the urge to chase growth through expensive acquisitions.

For now, Steve and Gareth remain watchful rather than bullish. But as this discussion shows, even a troubled industry can offer insights and even opportunities if you look closely enough.

Listen to the full episode of Stocks Neat for the complete conversation and taste test.

Explore previous episodes here. We’d love your feedback. If you like what you’re hearing (and what we’re drinking), be sure to follow and subscribe.

You can listen to Stocks Neat on:

Spotify

Apple

Buzzsprout

YouTube

Get Ready, Get Excited: Preparing Our Portfolios for Cracks to Become Craters

In the September 2025 Quarterly Report Chief Investment Officer, Steve Johnson, asked a simple question. “With optimism spreading, should our concern levels be rising?” It captured the mood in the team at the time. When confidence becomes widespread, caution becomes more important.

Here at Forager, the investment team has been proactively and successfully preparing both Fund portfolios for potential market volatility by raising cash and shifting toward defensive businesses. This puts the Funds in a position to capitalise on opportunities when they emerge. Might we get our chance soon?

Preparing Our Portfolios for More Turbulent Markets

Long before any volatility appears on screens, the investment team is already doing the work behind the scenes. That preparation has been underway for some time. We have been trimming or exiting positions that have run too far and taking profits when prices no longer reflect long-term value.

Two very clear examples come from the Forager Australian Shares Fund. Catapult (CAT) and Bravura (BVS) were both strong contributors to returns this year. We sold out of both when their valuations became stretched. Not because the businesses had deteriorated, but because the prices no longer made sense for patient, long-term investors.

We have also been lifting cash levels in both portfolios so we have the ability to act when opportunities return. Alongside that, we have tilted both portfolios towards some steadier, more defensive businesses that tend to hold up well when things get bumpy.

This is not about forecasting. It is about being ready. Our approach relies on a disciplined process. When good businesses become too expensive, we step aside. When they fall back to sensible prices, as some are beginning to do, we want to be in a position to own them again. Flexibility is a key part of our investing philosophy and holding a little more cash gives us room to move when the right chances appear.

Not all share price falls are created equal

Although we are nowhere near peak pessimism, there have been enough recent moves to suggest a shift in tone.

Some companies fall because their underlying businesses are simply not good enough. Weak balance sheets, poor strategic decisions or ineffective management eventually show up in the numbers. When these prices fall, they often stay low. We aim to avoid these businesses altogether.

Then there are the much better businesses. The ones with strong fundamentals, loyal customers and the ability to grow for many years. Prices for these companies can fall too, usually for reasons that have little to do with the underlying business.

Sometimes they have simply run too far ahead of their actual earnings. Sometimes short-term sentiment takes over. The underlying business remains sound but the share price takes a hit.

Since our exits, share prices for both Catapult and Bravura have fallen around 25 to 30%. They have plenty of friends at the moment. Life360 (360) has been on a similar journey. While we owned this company for a while back in 2020, we missed its most recent ascent. The business has grown and improved and we would love to own it again, at the right price.

Internationally, we are seeing a similar pattern. Index returns look healthy on the surface, yet many individual companies have been hit hard. The headline numbers are being propped up by a small group of winners, particularly in the Nasdaq 100, where 15% of companies are trading at levels more than 50% below their all-time highs.

This is exactly the sort of cycle we hope for. Strong businesses become expensive, we exit, then a pullback gives us a fresh look.

Get ready, get excited

Even after their recent pullbacks, share prices for Catapult, Bravura and Life360 remain well ahead this calendar year, up 36%, 15% and 75% respectively. Whilst there have been some cracks emerging, this is nowhere near peak pessimism. What matters is that we are ready if conditions do become more challenging. Let’s hope that these cracks become craters so we can put that cash to work.

Why Do So Many Forager Investments End in Takeovers?

If you’ve followed the Forager Australian Shares Fund for a while, you might have noticed a theme: a surprising number of our investments end up acquired by another company. From small technology firms to niche industrials, our portfolio has been a fertile hunting ground for private equity firms and larger companies looking for attractive acquisitions on the ASX.

The prevalence of takeovers in the portfolio is not by design - at least, not entirely. And they haven’t all been great investments. On more than a few occasions - Bigtincan and Whispir come to mind - an eventual takeover was simply relieving us of our misery. Even for the losers, strategic appeal can provide important downside protection.

In June we wrote about five Australian small cap takeover candidates to complement the three portfolio investments already under takeover at the time. Mining technology business RPMGlobal (RUL) has been the first of these to receive a formal bid. At the time we wrote:

“The potential for a takeover at a healthy premium is a nice kicker when the fundamentals are strong, the valuation is attractive, and the assets have strategic value. With our focus on the unloved and underappreciated, we think we hold a few of those. Let’s see if would-be acquirers agree.”

In the case of RPMGlobal, global mining equipment behemoth Caterpillar Inc (NYSE:CAT) very much agreed. Caterpillar has bid $5.00 per share in a deal which values RPMGlobal at over $1.1bn, or nearly 15 times recurring software revenue. The Forager Australian Shares Fund first bought shares at $0.77 six years ago.

Today’s piece is about how to find the next RPMGlobal.

Buying it cheap

The first ingredient of a highly successful takeover candidate is to buy it cheap to start with. When Forager first invested in 2019, RPMGlobal was an underappreciated business with world-class mining software, recurring revenue from a growing global client base and a management team intent on reshaping the company.

A transition from multi-year software licences to annual recurring software subscriptions was a handbrake to revenue growth and profitability. The value in the company was hidden. Once the subscription transition was complete, revenue growth and free cashflow would be plain to see.

Buy a business you want to own anyway

In the last three years subscription software revenue more than doubled. Very few clients turned the software off. And existing clients were spending more on their software every year.

Source: Bloomberg

While we waited, RPMGlobal grew, generated cashflow and bought back its own shares. The longer it took, the more we stood to make when a takeover finally arrived.

If you are happy owning the business anyway, you are far more likely to end up with an outstanding result on takeover.

The right management team

RPMGlobal’s management executed superbly during our period of ownership. All with one eye on an eventual sale, they simplified the business, sold non-core divisions, and invested heavily in software development. The transition to a subscription-based model built predictable, high-margin revenue streams and demonstrated the scalability of the product suite.

By the time Caterpillar came knocking, RPMGlobal had become a global leader in mine scheduling, mining equipment management and mine financial software. This is exactly the kind of asset a company like Caterpillar could integrate into its digital ecosystem. Not many CEOs want to work themselves out of a job, but Richard Mathews had prior form and enough shares to make the hard work worthwhile.

Strategic value

The final and most important ingredient is for the business to be worth more to someone else than it will ever be worth on the stockmarket. For Caterpillar, the acquisition strengthens its position in mining technology and provides access to RPMGlobal’s best-in-class software and deep customer relationships across the mining industry.

And for RPMGlobal shareholders, being listed is expensive. The board, listing costs and corporate overheads chewed up roughly two thirds of RPM’s operating profits in the 2025 financial year. Not only does Caterpillar get a strategic asset, it won’t incur many of those costs, making the acquisition price a lot more palatable.

For shareholders, the $5.00 per share offer represents a significant premium and an excellent crystallisation of value. For Caterpillar, it makes sense too. The best deals often do.

If you'd like to find out more about the Forager Australian Shares Fund, you can do so here.

DISCLAIMER: The Trust Company (RE Services) Limited (ABN 45 003 278 831, AFSL No: 235150) is the responsible entity and the issuer of the Forager Australian Shares Fund (ARSN No: 139 641 491). You should consider the product disclosure statement (PDS), prior to making any investment decisions. The PDS and target market determination (TMD) can be obtained here. General advice only and does not take into account the objectives, financial situation or needs of investors. Past performance is not indicative of future performance and the value of your investment can rise or fall.

Special Episode | GDG's Grant Hackett on Purpose, Pressure and Leadership

High Performance In and Out of the Pool

From Olympic gold to the ASX 200, Generation Development Group CEO Grant Hackett joins Steve Johnson for a special episode of Stocks Neat.

They discuss Grant’s journey from elite sport to business leadership, the importance of purpose beyond success, and how lessons from swimming translate into building a $3 billion company.

As Grant shares: “You’re retired to something, not from something.”

The conversation also dives into Generation Development Group’s core businesses, from investment bonds and annuities to Lonsec and the rise of managed accounts, and how the company is navigating growth, regulation, and leadership under pressure.

Make sure to stick around to the end of the podcast, for a candid talk between Steve and Grant.

Explore previous episodes here. We’d love your feedback. If you like what you’re hearing (and what we’re drinking), be sure to follow and subscribe – we’re doing this every quarter.

You can listen on:

Spotify

Apple

Buzzsprout

YouTube

The Land of the Rising Return: Forager in Japan

In the latest Stocks Neat episode, Steve Johnson, Gareth Brown and Isabella Foley dive into Japan’s corporate transformation — from shareholder returns and buybacks to digitisation and the demographic shifts reshaping opportunities.

With Japan now a significant part of the international portfolio, the team shares where they’re finding value and why some of the most interesting ideas are hiding in plain sight.

“It’s been like a snowball that’s been pushing across a flat surface for a long period of time. It’s finally started to gather some momentum.” – Steve Johnson

Explore previous episodes here. We’d love your feedback. If you like what you’re hearing (and what we’re drinking), be sure to follow and subscribe – we’re doing this every quarter.

You can listen on:

Spotify

Apple

Buzzsprout

YouTube

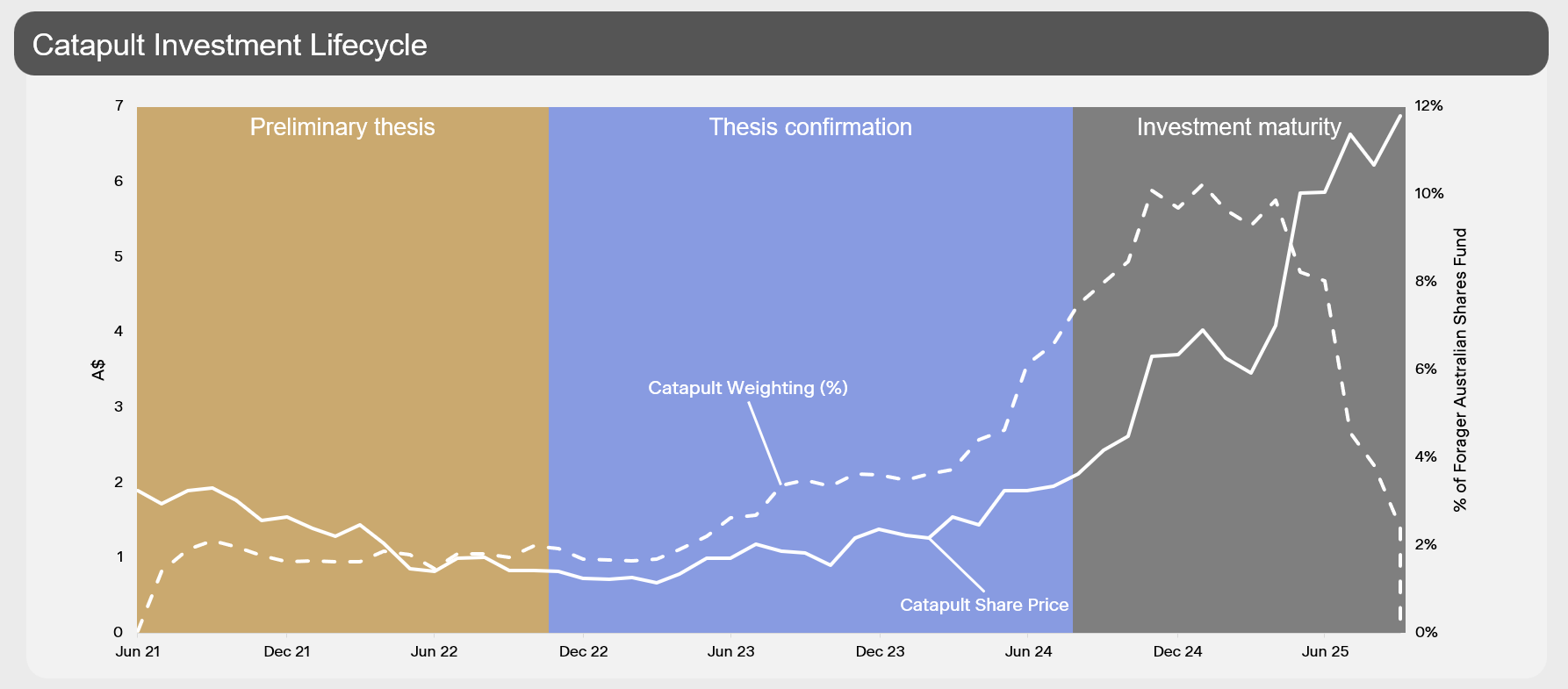

Moving on from Catapult

Investing in unloved and underappreciated stocks is rarely comfortable. It often means doubting what other investors believe and backing ideas others dismiss. Our journey with Catapult Sports (CAT) was an exercise in patience and conviction that has now rewarded us handsomely. Yet this investment has now come to an end - the Fund sold the last of its shares in Catapult this week.

Forager’s first purchase of Catapult shares was June 2021 at $1.90 per share. Almost two years later, in April 2023, we were adding to the Fund’s investment between $0.70 and $0.80. With the share price north of $6, it has been a wonderful investment for Forager investors and anyone who played along.

It’s not the first investment on which we have made those sorts of returns. Gentrack (GTK) and RPMGlobal (RUL) have been similar-sized winners in recent years. Yet Catapult is the stock where we best applied 16 years of lessons to truly optimise a successful investment:

1. Low Initial weighting. The initial weighting was less than 2% for several years. This allowed us to more easily cut the investment with limited damage had our contrarian view been proven wrong.

2. Adding on strength. We added to that low initial weighting on good news, even after the price had risen. While paying $1.50 a share after seeing $0.70 isn't easy, building confidence in a thesis allows for a crucial counter to the risk-minimisation of a low initial weight. At its peak, Catapult was more than 10% of the Fund.

3. Capturing the upside. We held a higher-than-usual portfolio weighting to capture the maximum upside as Catapult moved from a relatively unknown stock to an ASX300 member with major investment bank research coverage.

4. Winding back. And yet we are valuation-driven investors. There is a point when higher stock prices create a valuation at which future returns no longer meet our minimum thresholds. This is where we have arrived with Catapult.

And so our journey has come to an end.

In the weeks after recording Livewire’s innovation episode of Buy Hold Sell, Catapult was a surprise replacement for Gold Road in the ASX200 index. That sent the share price up another dollar, leaving the company sporting a market capitalisation in excess of $2bn. This price-agnostic index buying was a good opportunity to exit the last of our holding.

It still has the same bright future we hoped for when making our first investment four years ago. But today’s valuation reflects a bright future and a bit more. We have barely changed our numbers over the four-year holding period, meaning time and sentiment alone have driven the share price to its current level.

There are plenty of scenarios where Catapult shareholders do well from here and I would love to see this Aussie business become a massive global success. Catapult is our best ever example of optimising the profit from a successful investment. But at Forager we excel at finding the unloved and underappreciated, and at these prices it is time for us to focus on finding the next one.

To find out where Forager is redeploying its capital in today’s market, register below for our upcoming September quarterly report

Where We’re Finding Opportunities in Japan

Reform is the backdrop, but this isn’t about just owning the index. Japan has around four thousand listed companies and plenty of them are cheap for a reason. Our job is to find the ones with tailwinds strong enough to matter.

Three stand out. Labour shortages, legacy IT systems, and a culture finally willing to change. That combination is creating opportunities in areas that have been stagnant for decades.

The Digital Cliff

Japan still spends around 90% of its IT budget patching up old systems. More than 60% of corporate IT platforms are over twenty years old. Policymakers call it the ‘2025 digital cliff.’ These systems are past their use-by date. At some point they will break, and replacement is inevitable.

At the same time, there aren’t enough workers to go around. The population is shrinking, the workforce is shrinking faster, and wage growth is the highest it has been in decades. If you’re running a business, that means you have to do more with less. Productivity tools are no longer a nice-to-have. That urgency is fuelling demand for software and platforms.

Back-office accounting software hardly sounds exciting. But OBIC Business Consultants (JP:4733) has turned it into one of the better businesses in Japan. Its Bugyo suite handles accounting, payroll, tax and HR for hundreds of thousands of small and medium-sized enterprises. Once embedded, clients rarely leave, delivering margins that most global software firms would envy. The company has been migrating its loyal customer base from on-premise systems to the cloud over the past few years. That allows for upselling of new services and deepens its moat. Japan’s digital cliff is OBIC Business Consultant’s opportunity.

Solutions for Large Corporates

At the other end of the spectrum are Japan’s large corporates, very slow to change and still reliant on systems written decades ago. This is where micro-cap company DreamArts (TSE:4811) comes in. Its SmartDB no-code platform allows frontline staff to build the tools they need without waiting on IT teams. Other products target communication and workflow bottlenecks across banks, manufacturers, and government agencies. These projects can require decade long commitments due to complexity. The cost of inefficiency in these organisations is enormous, and DreamArts offers a rare path to improvement.

Recruitment in Japan is Changing

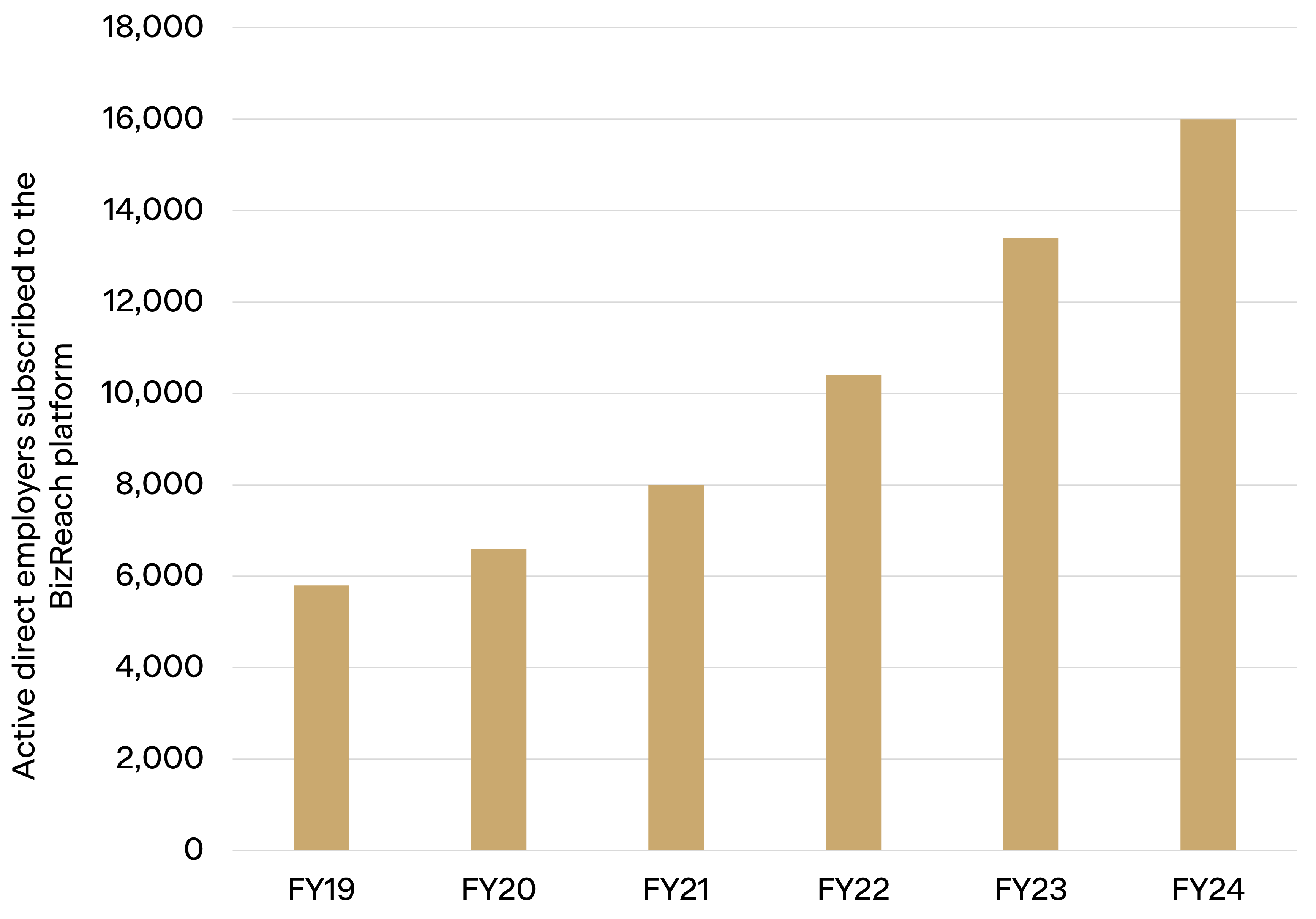

Labour shortages and rising wages are also reshaping the recruitment industry. Visional (TSE:4194), through its BizReach platform, has become the dominant channel for professional, mid-career hiring. The platform has a leading market share in Japan, with a user base of over 2.5 million high-income white-collar job seekers. Growth has been consistent, margins strong, and management disciplined in reinvestment. For a business compounding earnings at around 20%, the valuation looks undemanding.

The cultural backdrop in the labour market matters. Lifetime employment is becoming less entrenched. One in three graduates now expects to switch jobs throughout their career. Prospective job changers have been on the rise since Covid and exceeded 10 million individuals for the first time in 2023. The era of major job transitions has begun. Employers and recruiters desperate for talent are paying to access Visional’s growing pool of eligible candidates. And every new participant makes the platform more valuable for the next one. It’s a network effect.

Digitisation in Health

Healthcare is another sector ripe for digitalisation. Japan’s home nursing market is expanding rapidly as the population ages and hospitals push patients into home-care. Yet most of the country’s 17,000 nursing stations still run on paper or Excel. Nurses spend up to a third of their time on administration, worsening an already severe labour shortage.

This is where eWeLL (TSE:5038) has carved out a niche. Its iBow platform is Japan’s leading cloud product built specifically for home-visit nursing, covering everything from medical records and care planning to scheduling, billing, and compliance. The business model is simple and aligned: stations pay a base subscription plus a small per-visit fee. More patient visits mean more revenue for both sides. The product is sticky. Churn is close to zero. Today iBow supports more than 3,000 nursing stations and 740,000 patients, giving eWeLL a scale advantage and a dataset that rivals can’t match. Penetration is still only about 18%, leaving a long runway as the market continues to grow.

What Forager Owns

The Fund owns seven Japanese software companies, each serving a different end market but all benefiting from reform, an ageing workforce, and the urgent need to digitise. They are not just cheap stocks. They are growth businesses backed by long-term structural tailwinds.

For Forager, that is the attraction. Japan offers the combination we look for: undervalued markets, visible change, and companies we can meet, question, and back for the long haul.

That is why almost one-fifth of the Forager International Fund is invested in Japan.

If you are interesting in getting some exposure to Japan, you can apply for the Forager International Shares Fund here.

Japan’s Snowball Moment

Last Monday, Portfolio Manager Harvey Migotti and I (Bella Foley) returned from ten days in Japan.

Our schedule was packed: the Mizuho Japan Alpha Conference, the Launch Point Small Cap Conference, and more than 30 management meetings. Back in Sydney, we joined Daiwa’s Japan Exchange Group Conference, where we met with Hiromi Yamaji-san, CEO of the Tokyo Stock Exchange.

The contrast with five years ago was stark. Conference rooms that once sat half empty were overflowing. International investors that ignored Japan for decades were now showing up in force. And the reason is simple: change that has long been promised is finally visible in company results, capital allocation, and stock prices.

Increasing Exposure to Japan

Two years ago, Japan was just 5% of the Forager International Shares Fund. Today it is nearing 20%. That shift reflects not just what’s happening in Japan, but what isn’t happening elsewhere. US markets remain our anchor at 45% of the Fund, but valuations there are stretched. Japan, by contrast, trades on 16 times forward earnings, with half of listed companies still below book value. Cheap, under-owned, and now reforming – that’s the combination that has pulled us deeper into the market.

The turning point came in March 2023, when the Tokyo Stock Exchange demanded that companies become “conscious of cost of capital and stock price.” It sounded vague, but the effect has been profound. Yamaji-san described it as a giant snowball that had been pushed across a flat surface for years. Slow, heavy work – but now it is rolling downhill under its own momentum.

Peer pressure is doing the work. More than 90% of Prime market companies have now disclosed improvement plans. Those with credible strategies have outperformed sharply, returning 67% since March 2023, versus just 17% for those without. The market is rewarding better governance, and management teams are responding.

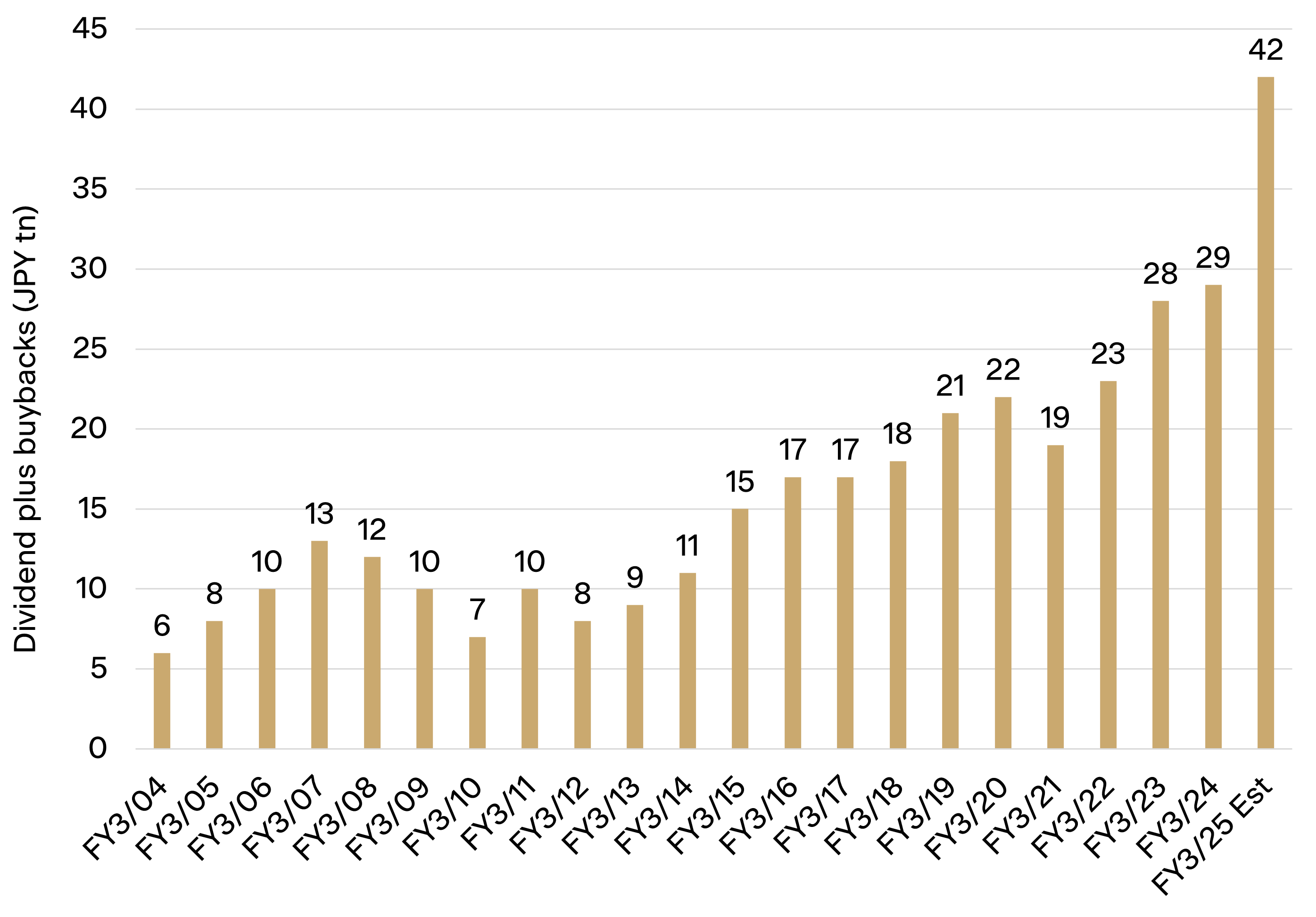

The numbers on capital returns are extraordinary. Buybacks doubled to ¥20 trillion in 2024, and another ¥14 trillion has already been announced this year. Dividends plus buybacks now return about 5% of market cap annually, double the US equivalent. Crucially, more companies are cancelling the shares they repurchase, locking in permanent earnings accretion.

Activism and M&A increase the Snowball Effect

Reform has opened the door to activism and M&A. Domestic investors are pushing harder, with CEO approval votes slipping toward 50% in some companies. Poison-pill defences have largely disappeared.

Foreign bids are also flooding in. Overseas firms lodged 157 takeover proposals in the first eight months of 2025, already close to last year’s record. Policy changes now require boards to give “sincere consideration” to credible offers, limiting the ability to brush them aside. For the first time in decades, Japan is an open field for corporate activity.

Demographics Forcing the Change

Japan’s demographics, usually discussed as a headwind, are in fact forcing change. More than 2.4 million SME owners are over 70, and half have no successor. Left unchecked, that would mean millions of lost jobs and a significant hit to GDP. The obvious outcome is consolidation. For listed companies with balance sheet strength, opportunities to acquire are multiplying.

At the same time, labour shortages are driving productivity gains. Wage negotiations in 2024 delivered 5% increases, the largest in 30 years. In Japan, higher wages often coincide with higher margins, as companies rationalise and modernise to cope.

This combination – governance reform, corporate activity, and demographic pressure – is what makes this Japan cycle different. The snowball has started rolling, and for investors prepared to do the work, it is gathering speed.

If you are interested in making an application into the Forager International Shares Fund, you can do so here.

Boring businesses, Exciting Turnarounds

In a world with market chatter often centring around the most exciting theme of the day, three of the Forager Australian Shares Fund’s better contributors over the past year operate in industries that rarely make headlines. They fix cars, sell motorbikes and dig rocks. But each of them delivered meaningful changes and have won back investor appreciation.

AMA Group: Finally Fixed

Few companies on the ASX have a history of disappointing investors as consistently as AMA Group (AMA). The panel repair business was weighed down by high debt, constant management turnover and multiple inadequate capital raisings. We had followed the story for years and even got burned previously. But in July 2024, the turnaround began.

AMA finally raised the capital it needed. This was a significant amount, which came with some dilution of existing holders, but cleared the balance sheet of its problems and gave the business runway to operate. With liquidity restored, the focus turned to fixing operations.

AMA Group finally raises the capital it needs

Source: Bloomberg

Capital SMART, the company’s fast-turnaround repair division, began to show signs of life. Margins in the broader collision repair business also started to improve. A new CEO took the helm and a credible turnaround plan was implemented. At the 2025 financial year results management’s preferred measure of profitability had risen 38%.

We participated in the capital raise at 4.2 cents. The share price responded quickly, ending last financial year up 150 percent from the raise price. We are only part way through the company’s turnaround, but the structure is now in place for sustained recovery. Sometimes the hardest part is survival. AMA has cleared that hurdle and we believe it is looking towards a brighter future.

MotorCycle Holdings: A Rare Opportunity at the Bottom

Motorcycle Holdings (MTO) has not always been well-loved by the market. Only 15 months ago the retailer and wholesaler of motorcycles and accessories was caught up in a fund liquidation, driving the share price to under $1 per share. Liquidity was low and sentiment was poor. We believed the market had overreacted and added significantly to our position.

This wasn’t a classic turnaround story in the operational sense. While the motorcycle dealership business was under pressure, the wholesale distribution of CF Moto motorcycles was going well. Net profit rose 28% in the 2025 financial year.

Then came the moment of transformation. On the second-last day of the financial year, the company announced the acquisition of several dealerships from its closest competitor. The purchase was highly strategic. It took Motorcycle Holdings to an estimated 20 percent market share in new Australian motorcycle sales. The economics of the deal look attractive, especially after factoring in the supply of the company's wholesale accessories through the new dealerships.

By the end of August the stock had more than tripled from its lows and finished above $3.50 per share. Profitability in the core dealership should improve from low levels, the CF Moto segment should continue to grow and the new acquisitions should add meaningfully to profits. Despite the business still having a market capitalisation below $300m, investors are now more aware of its potential. We have actively managed the weighting of this investment in the portfolio and currently retain a small investment as higher prices have reduced our perceived future returns.

Perenti: Boring Is Beautiful

Mining services is not an industry that gets many overly excited. Investors had long been skeptical of the ability of mining services businesses to generate sustainable free cash flow. The sector was known more for losing money on poorly priced contracts and chewing through capital for new equipment.

So it was exciting to see Perenti (PRN) delivering on exactly what it promised.

The company has spent the past few years improving its margins, reshaping its stable of contracts, and staying disciplined on capital spending. In the 2025 financial year, Perenti guided to more than $150 million of free cash flow. The business eventually achieved $195m.

The market finally noticed. Steady operational delivery and consistent performance resulted in quickly improved valuations. The share price has risen more than 140% over the last year, and the Fund exited its investment part way through the year. The Fund remains invested in fellow mining services stock Macmahon (MAH), which has also seen its share price rally through the year.

Why These Turnarounds Worked

While these companies operate in disparate industries they share a few key factors.

Firstly, the businesses started off deeply out of favour. Valuations had fallen to extreme levels, below six times forward earnings for each in the middle of 2024.

The businesses also achieved the milestones investors wanted to see. For AMA, it was a well executed large capital raise. For Motorcycle Holdings, it was earnings stability and debt reduction. And for Perenti, the reliable delivery of cash flows.

Thirdly, management teams executed. They didn’t just talk about change. As execution improved, so did investor willingness to back the management teams to continue delivering good results in the future.

There will always be businesses that get left behind by the index giants and forgotten by institutional investors. These unloved and underappreciated businesses can deliver some fantastic returns. And that is anything but boring.

If you are interested in making an application into the Forager Australian Shares Fund, you can do so here.

Small Caps Turning the Corner

For years, small and mid-cap stocks have lagged their larger peers. Investors gravitated toward the perceived safety of big names, leaving many smaller companies overlooked and undervalued. The result has been a significant stretch of underperformance from small-caps relative to their large-cap peers, both in Australia and globally.

At Forager, we’ve been talking about this divergence for some time. However, we’ve also been clear: market-wide trends don’t stop us from finding opportunities. This environment created a fertile ground for stock pickers and we have still been able to find opportunities in individual businesses. So even through years of relative index underperformance, we’ve been able to build portfolios of stocks that have outperformed.

And now small-cap underperformance could be turning around.

The Tide is Starting to Shift

Over recent months, small and mid-caps have begun to outperform. Overseas, this has been most visible in global SMID (small-to-mid cap) indices, where investor appetite is returning after years of neglect. In Australia, reporting season is providing hard evidence that many companies at the smaller end are not only surviving but thriving.

The numbers tell the story. In August, the Small Ordinaries Accumulation Index returned a whopping 8.4%, more than double the 3.2% return from the All Ordinaries Accumulation Index. And it’s not just a one-month anomaly. Over the 12 months to 29 August 2025, small caps have delivered a 23.5% return, comfortably ahead of the All Ords’ 15.0%.

This is significant. Small caps tend to move in cycles. When confidence is high, they can deliver outsized returns. When risk appetite is low, they lag. The long run of underperformance has meant valuations have reset to more attractive levels. It doesn’t take much good news to move share prices meaningfully.

What Reporting Season is Showing

As reporting season rolls on, a common theme is emerging: expectations are low, and modest results can be nicely rewarded.

Experience Co (EXP) is a good example of this shift in sentiment. The company had already flagged its results to the market, so there were no surprises when the numbers were released. Even so, the share price jumped more than 20% in the aftermath. That kind of reaction highlights how investors are not only rewarding strong results but are also willing to re-rate smaller companies when confidence starts to return.

On the other side of the ledger, several large caps have stumbled badly – including names like James Hardie (JHX) and CSL (CSL). In total, seven of the top 50 listed stocks saw share price falls of 10% or more on the day of results, compared to one or two in reporting seasons past.

It’s a reminder that volatility isn’t confined to smaller companies. Even market giants can deliver nasty surprises, and size alone doesn’t shield investors from risk.

That contrast makes the current environment all the more interesting. While some large caps are struggling to meet expectations, smaller companies are surprising on the upside, and the market is starting to notice.

Double Tailwinds for Forager

Forager’s approach has always been to look where others aren’t. We focus on the unloved and underappreciated. In recent years, the lack of interest in small-caps has suited us well, providing plenty of bargains and strong returns from stock picking. In truth, we haven’t been in a hurry for the broader underperformance to reverse.

But markets rarely deliver exactly what you want. Falling interest rates and weakness among large-caps could quickly drive a reversion to more typical valuation relativities between big and small companies. The Small Ordinaries Index is still trailing significantly over five years, but the past 12 months show just how quickly the gap can close.

As always, investing in small and mid-cap companies carries risks, including the potential for higher volatility, lower liquidity, and business models that may be more sensitive to changing economic conditions. As with all investments, returns are not guaranteed and capital is at risk, so it's important to ensure that this part of your portfolio aligns with your risk tolerance and long-term goals.

For diversified portfolios, however, small caps have an important role to play – and this may be a moment where waiting on the sidelines carries its own risks.

If you are ready to begin your journey into investing in small-caps, you can apply for both of our Funds online.

Why Global Small Caps Deserve a Place in Your Australian Portfolio

When you’re an Australian investor, it’s easy to fall into the “home bias” trap. The ASX feels familiar, the companies are in your backyard, and there are tax advantages like franking credits that make it even more appealing. But sticking too close to home also comes with risks - limited sector diversity, concentration in a handful of large banks and miners, not to mention exposure to a single economy and currency.

Adding global stocks, especially small and mid-caps to your portfolio could help balance those risks, while opening up a world of opportunity. This is why:

Access to Sectors and Trends You Can’t Find on the ASX

Australia’s stock market is heavily skewed toward financials and resources, leaving big gaps in areas like technology, healthcare, and consumer brands. Global small caps could give you exposure to innovative companies in niche industries that simply don’t exist in Australia.

These businesses often operate in growing markets and can scale quickly, making them attractive for long-term investors looking for growth beyond the ASX’s usual suspects.

Diversification Beyond the Big Banks and Miners

Even the strongest home market has its limitations. Australian investors who stay local end up with a portfolio highly sensitive to domestic economic cycles, housing market risks, and commodity price swings.

Global small caps may spread that risk across countries, currencies, and economic drivers. When one market slows, another might be accelerating. That kind of diversification can smooth out your returns over time.

Inefficiencies Create Opportunity

The global small and mid-cap universe is huge. Thousands of companies, many flying under the radar of large institutional investors and analysts. Less coverage means less efficient pricing, which is exactly where active managers like Forager thrive.

These overlooked businesses may be mispriced relative to their fundamentals, creating opportunities to buy quality companies at attractive valuations.

Different Return Drivers from Global Large Caps

You might already have exposure to global large caps through an ETF or your super fund. But large-cap multinationals are more correlated with global macroeconomic trends and tend to move in sync with major indices.

Small and mid-caps, on the other hand, are often driven by company-specific factors, such as launching a new product, entering a new market, or being acquired. This may give them a return profile that’s less tied to the overall market, adding a new dimension to your portfolio.

Risks to Consider

While global small-cap stocks can offer compelling growth opportunities, they also come with specific risks. These companies tend to be more volatile than larger, more established businesses and may be more sensitive to changes in economic conditions or investor sentiment. They can also be less liquid, meaning it may be harder to buy or sell positions without affecting the price.

In addition, investing in international markets introduces currency risk and exposure to different regulatory and political environments. As with all investments, returns are not guaranteed and capital is at risk, so it's important to ensure that this part of your portfolio aligns with your risk tolerance and long-term goals.

How Global SMIDs Might Fit Alongside Australian Shares

Global small caps aren’t a replacement for your Australian shares - they can be a complement. A balanced portfolio might combine:

- Australian equities for income (franking credits, distributions) and exposure to familiar sectors

- Global large-caps for blue-chip stability and mega-trend exposure

- Global small and mid-caps for growth, diversification, and access to niche opportunities

This blend could help you manage risk while tapping into growth stories you simply can’t find in one market alone.

Why Now?

Right now, global SMID caps are trading at very attractive valuations relative to their larger peers. Investor sentiment has been cautious, creating opportunities to buy quality businesses at a discount.

For long-term investors, that’s the kind of dislocation that can set up strong future returns if you’re willing to look beyond your home market.

At Forager, we’ve built the Forager International Shares Fund specifically to hunt for these types of opportunities - smaller, often overlooked companies with the potential for long-term growth. By pairing it with the Forager Australian Shares Fund, you get the best of both worlds: local familiarity and global diversification.

Smoothing the Ride: Forager’s Distribution Policy

Over the past few years, following investor feedback, Forager and the Responsible Entity introduced new distribution policies for the Forager Australian Shares Fund and the Forager International Shares Fund, aimed at delivering a smoother and more predictable income stream for investors.

What Changed?

Under the current policies, the Funds both:

- Target an annual distribution yield of approximately 4%, based on the Fund’s Net Asset Value per unit at the beginning of the financial year.

- Pay ordinary distributions semi-annually.

- Pay special distributions in years where the Fund’s taxable income materially exceeds the amount paid via ordinary distributions, ensuring that at least 50% of taxable income is distributed in cash in those years.

Why the Change?

The previous approach to distributions meant payments could be volatile - large in years of high realised gains, and minimal in low-income years. The new policy smooths this volatility, offering investors more consistent cash flow. Forager believes this makes the Fund more attractive to those seeking a steadier income stream, while still preserving the Fund’s focus on long-term capital growth.

It’s important to note that this change did not and does not alter the Fund’s investment objective or the nature of its returns, which are still expected to be primarily driven by capital gains and may remain lumpy year-to-year.

What About Compounding?

Investors who don’t need regular income can continue to reinvest their distributions via the Distribution Reinvestment Plan (DRP). This allows for automatic compounding of returns. DRP preferences can be managed through your Automic account under “Reinvestment Plans”.

Tax Implications and the Role of AMIT

The Fund operates under the Attribution Managed Investment Trust (AMIT) regime. Under AMIT, investors are taxed on their share of the Fund’s taxable income, not just what they receive in cash.

This means:

- In years where taxable income exceeds cash distributions, you will pay tax on the full taxable income and the difference between that amount and the cash distribution is added to the cost base of your investment, reducing capital gains when you sell.

- In years where distributions are greater than taxable income, you pay tax on the lower amount in that year and the difference between the taxable income and the cash distribution reduces your cost base, potentially increasing capital gains in the future.

Your annual AMMA (Annual Member Statement) will outline these adjustments for your tax return. The new policy does not change your total taxable income, just the timing and format of the cash distributions.

A Reminder

As always, investors should consult a financial adviser or tax professional before making decisions based on distribution policies or tax impacts.

Corporate Japan gets a makeover

After decades of frustrating capital allocation and entrenched complacency, Japanese corporate governance is finally undergoing meaningful change, and it’s starting to show up in investor returns.

The Tokyo Stock Exchange’s (TSE) ongoing reforms are proving a powerful catalyst. In 2023, the TSE launched its “comply or explain” campaign, urging companies trading below book value to improve capital efficiency or publicly justify why they aren’t. The message was clear: lift return on equity, shrink bloated balance sheets, unwind cross-shareholdings and return capital to shareholders. Companies that ignore this pressure risk being publicly named, or increasingly, targeted by activists. We’re still in the early innings of what is likely to be a multi-year shift in capital allocation across corporate Japan. Buybacks have doubled over the past 12 months, and more companies are setting multi-year capital return plans. Yet more than half of Japanese companies still trade below book, suggesting the reform story has further to run.

Topix - Total aggregate dividends & buybacks by year

For active managers, it’s a rare alignment of top-down reform and bottom-up opportunity. Japanese software, in particular, has been fertile foraging ground. The country still lags global peers in cloud adoption, with many businesses relying on outdated infrastructure and legacy systems. As digitisation gathers pace and governance standards improve, the runway for high-margin, capital-light growth companies is expanding.

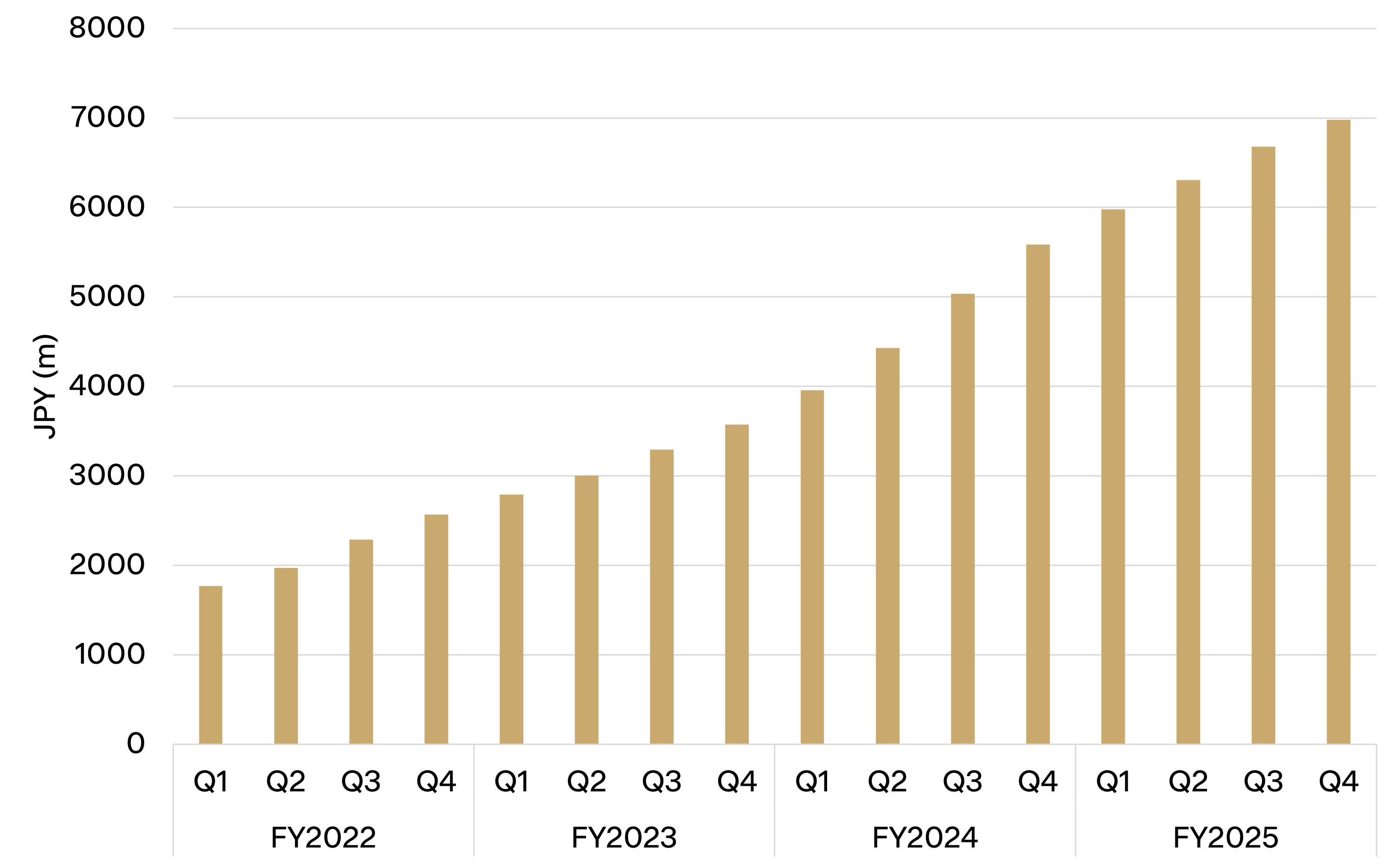

Separately, the government is pushing hard on cashless payments, aiming to lift penetration to 80% from around 40% today, well below the 60-70% levels already reached in most Western markets. E-commerce is similarly underdeveloped, accounting for just 9% of retail sales versus 15% in the US and more than 25% in the UK. These structural shifts are creating multi-year tailwinds for a small but growing group of domestic software champions, including one of the Fund’s holdings, GMO Payment Gateway (JP:3769), a leading Japanese payments processor serving both online and offline businesses.

Two more of the Fund’s top contributors this year were Japanese software businesses benefiting from the country’s accelerating digital transformation. OBIC Business Consultants (JP:4733), a longerterm holding, is a conservative, highly profitable software company specialising in accounting and payroll solutions for small and midsized businesses. It added 1.0% to returns as it continued delivering steady, software-driven growth with strong margins. Shift (JP:3697), a newer addition, is Japan’s leading independent provider of software testing and quality assurance services. It’s a capital-light business scaling quickly in a fragmented market, and it contributed 1.1% to Fund performance before being sold.

OBIC Business Consultants cloud revenue by quarter

Japan’s labour market is also changing. A shrinking workforce, rising wages and a shift away from lifetime employment are pushing large corporations to modernise HR systems and embrace mid-career hiring. That’s creating a fertile environment for Visional (TSE:4194), an HR technology company offering platforms for recruitment and workforce management.

Despite its short tenure in the portfolio, Visional has already made a meaningful contribution. Its two core platforms, BizReach (Japan’s leading direct recruiting site for high-income professionals) and HRMOS (a cloud-based HR suite), serve over 16,000 paying clients and are building a sticky ecosystem across HR workflows.

Visional subscribers are growing steadily

It’s exactly the kind of capital-light, high-margin software business that we like. Growth has been consistent, margins strong, and management disciplined in reinvestment. For a business compounding earnings at around 20%, the valuation still looks undemanding. Visional has all the ingredients of a long-term compounder, and the broader structural tailwinds in Japan are only just beginning. Visional is now a top 10 holding in the Fund.

Between structural reform, improving governance, rising capital returns and an underappreciated runway for digital transformation, Japan is one of the Fund’s most attractive investment markets.

This is an excerpt from the June 2025 Annual Report

Feasting on the crumbs of passive giants

Passive flows and opportunity

Passive funds are the giants of modern markets, and they are here to stay. At Forager, we have taken the view that it is best to work with, not against, these funds. Therefore, long may they expand their footprint in equity markets.

Low-cost passive funds—and I’d include Australia’s superannuation giants in this category—are largely a force for good. Their relentless focus on costs has saved investors billions in fees. Given their enormous size, it’s entirely logical for them to stick to large, liquid companies. Take Australian Super as an example. As of 31 March this year, it had $367 billion in funds under management.

There’s simply no need—or point—for a fund of that size to venture into Australian small caps. Even if it invested $100 million in Forager’s

Australian Shares Fund, our 18% outperformance, would have earned its members just an extra 0.0049% for the year. Count the decimal points yourself.

Yet what’s logical for them creates opportunities for us. Think of it like the crumbs from a giant’s sandwich. For the giant, those crumbs are inconsequential. For a nimble ant, they can represent an enormous feast.

Over the past year, passive trends have helped us in three important ways.

Price-agnostic sellers

First, we’ve seen plenty of forced, price-insensitive selling at the smaller end of the market. This happens when stocks become too small for the giants’ portfolios, or when fund liquidations occur because super funds have given up on active small-cap managers.

Several high-profile small-cap fund closures occurred over the past 12 months as super funds pulled mandates. This created opportunities for us to add to existing investments at attractive prices—for example, in MotorCycle Holdings.

Companies at the bottom end of indices often experience sharp price declines as an initial, fundamentals-based drop is exacerbated by waves of passive selling. ASX-listed Johns Lyng, for instance, had a market capitalisation above $2 billion in mid-2022, enough for inclusion in the S&P/ASX 200 Index. By 31 March this year, it had been deleted from that index, with its share price down more than 75% from its peak(it bottomed, not coincidentally, on 9 April).

The business isn’t as good as investors thought when the share price was north of $9. But in our view, it’s not as bad as a $2 share price would suggest either. Most value investors would agree. Yet much of the price movement reflects passive investors who haven’t given valuation a moment’s thought.

Thematic waves

Another source of returns has come from the growing influence of thematic exchange-traded funds (ETFs). These funds allow investors to target sectors linked to themes like defence, cybersecurity, or artificial intelligence. While gaining popularity in Australia, they’re already significant players in US markets.

I’m far less convinced that thematic funds are a force for good. The whole point of index funds is to acknowledge that beating the market is difficult—and that keeping fees low matters most. Thematic funds charge significantly higher fees than broad index funds and appeal to investors who want to punt on the next hot sector. Almost by design, they attract a surge of money near the peaks and lose much of it at the lows.

That can create buying opportunities for us. Take Comfort Systems. I first met the management team of this NYSE-listed company at a broker conference in Chicago in November 2023. They provide a wide range of mechanical, electrical, and plumbing contracting services, specialising in HVAC systems.

My notes at the time read: Nice business, good management team, not sure about the special sauce, probably not cheap enough for us.

Forager’s International Fund Portfolio Manager, Harvey Migotti, met them again in November 2024. His assessment: Very good business, great management team, and strong long-term tailwinds from data centre construction and manufacturing returning to the US. The share price had doubled in the interim, but Harvey returned to Sydney convinced we needed to complete our research and be ready to act.

Then came Donald Trump’s renewed assault on global trade. Between 22 January and 4 April, Comfort Systems’ share price fell 46%. This company carries net cash on its balance sheet and has years of work locked into its order book. Yet when money flows out of the market, even good businesses get hammered. That’s when we get our chance to buy into companies with very bright futures. We’ve seen it across sectors—from building products to discretionary retail. When a theme falls out of favour, share prices across the sector tend to drop in lockstep, and the selling becomes indiscriminate.

Crumbs that grow large enough for giants

The third source of opportunity lies in identifying stocks that passive buyers will inevitably need to own a few years down the track. Consider the journey of Catapult Group.

In May 2022, the stock typically traded between $100,000 and $200,000 per day. Now, with Catapult firmly included in the S&P/ASX 300, it’s rare for daily volumes to fall below one million shares. With the share price up fivefold, that equates to more than $5 million worth of shares traded daily—and $10 million days are not uncommon.

Catapult’s business has progressed meaningfully, growing revenue nearly 20% per annum and delivering improved profitability. But index inclusion has been the mayonnaise on the sandwich. The increased liquidity firstly means larger small-cap managers can get interested. Then the passive funds need their share as well. Having traded at an undemanding two times revenue in 2022, Catapult now trades at a much more optimistic eight times the significantly higher revenue.

That “mayonnaise” will matter more as passive influence keeps growing. Forager will still invest in businesses that never make it into any index or super fund portfolio. Some of them, bought at the right price, will deliver excellent returns. There’s already plenty of money trying to arbitrage which stocks will be added or dropped whenever index providers rebalance. That’s not our game.

But when we’re looking three to five years ahead, we always ask: Could this business ever attract passive buying? Index inclusion can significantly amplify profits from successful investments. And at our relatively small size, it can add a meaningful boost to total portfolio returns.

The shift toward index funds and giant super funds isn’t likely to reverse. In aggregate, money will likely keep flowing out of the small- cap end of the market. For those of us with loyal, long-term clients, that makes for particularly fruitful foraging.

This is an excerpt from the June 2025 Annual Report and also appeared on Livewire Markets

Neat Reflection of 2025: Winners and Losers of the Passive Revolution

As the financial year wraps, Episode 37 of Stocks Neat takes a deep dive into the standout performance of Financial Year 25. Chief Investment Officer Steve Johnson is joined by Portfolio Managers, Gareth Brown and Alex Shevelev to discuss what drove results across Forager’s international and Australian funds — from Japanese software gems to ASX tech turnarounds and undervalued relics making quiet comebacks.

The conversation covers how passive flows are reshaping the investing landscape, the importance of preparedness in a momentum-driven market, and why the team is finding fertile ground in small caps despite years of pessimism.

“We are generally looking for pessimism, for volatility, for extreme events…preferably not too extreme, but it’s our kind of market.”

Explore previous episodes here. We’d love your feedback. If you like what you’re hearing (and what we’re drinking), be sure to follow and subscribe – we’re doing this every quarter.

You can listen on:

Spotify

Apple

Buzzsprout

YouTube

Why July Could Be a Smart Time to Invest

With the new financial year underway, here’s why savvy investors act now, not later.

The end of June might feel like a full stop at the end of the financial year. But for investors, July is often where the most thoughtful decisions begin. With a fresh tax year ahead, performance reset, and market jitters still looming large, it’s often the moment patient investors quietly get to work.

A Fresh Tax Year = A New Allocation Window

Many investors wait long after the End Of Financial Year (EOFY) to get their affairs in order, but July is often when the proactive ones act. New contribution limits, distributions out of the way and a clean slate mean decisions made now set the tone for the year ahead.

Early Action Means More Time in the Market

The earlier you invest, the longer your money is put to work. Starting in July doesn’t just mean getting in early, it means giving yourself the full financial year to benefit from compounding returns, reinvested distributions, and any opportunities that emerge along the way. For long-term investors, that extra time in the market can make a meaningful difference. It’s potentially a smart move that aligns your investment horizon with the financial year, setting you up for growth from day one.

Opportunity Often Looks Uncomfortable

Investors who act early in the financial year, especially when sentiment remains cautious, are often those who benefit most over time. At Forager, we’ve built our track record by focusing on parts of the market others tend to overlook. You’ll see that despite small-cap underperformance, the investment team have managed to find plenty of excellent opportunities during the FY25 financial year:

Right now, both domestic and global small and mid-cap stocks remain an especially fertile hunting ground. Our investment team is busy uncovering more new opportunities in Australia and overseas.

Of course, investing comes with risks. Markets go up and down, and there are no guarantees. But investing in July provides the greatest amount of time to weather any volatility that does happen during the financial year ahead.

Forager's Funds Are Positioned for What’s Next

We’ve made some bold investment decisions in recent months, moves that reflect where we see genuine long-term value, not where the headlines are pointing. We are also very happy about how our portfolios are positioned for the year ahead.

If you're already an investor, July is a great time to top up. If you've been watching Forager from the sidelines, maybe this is your year to jump in. Either way, now’s a smart time to act. Don't procrastinate, get your portfolio in order for the financial year ahead:

5 Small Cap Takeover Candidates

After a period of relative quiet, public merger and acquisition (M&A) activity on the ASX roared back to life in 2024. The number of deals hit a decade high. And there are good reasons to think the momentum will continue through 2025 and into 2026 — particularly at the small-cap end of the market.

A few macro tailwinds are aligning. Interest rates are heading lower, both in Australia and globally, improving the cost of capital and restoring confidence in risk-taking. Equity markets are surging again. And changes to Australian merger laws are set to come into force in early 2026, which may see deals accelerated to avoid a more cumbersome process under the new regime.

Global private equity still has near-record levels of “dry powder” to deploy. With the Australian dollar still weak and many small caps trading at steep discounts to historical multiples, the ingredients are there for a busy year.

Already in Play

Forager’s Australian Shares Fund only owns 31 stocks. Three of them are currently under takeover offers.

One well progressed is the battle for online bookmaker PointsBet (PBH). Japanese group MIXI (TSE:2121), armed with a cash-heavy balance sheet, is in the mix alongside Australian challenger Betr (BBT). In late April, Betr had little trouble raising $130m in fresh equity to fund the cash component of its tilt. Cost reductions across technology, marketing and labour mean the company expects more than $40m of synergies should the deal consummate. Mixi fired back with an upped $1.20 cash bid and will attempt to circumvent Betr’s pre-bid blocking stake by committing to an alternate structure if the current one (which requires 75% of voting shareholders to approve it) fails. That meeting will be held next week.

Natural disaster remediation company Johns Lyng (JLG) is in the crosshairs of private equity player Pacific Equity Partners (PEP). In an uncommon and shareholder unfriendly twist, investors are still waiting to learn the price PEP proposed to secure its exclusive due diligence. Less surprisingly, the proposed deal has been structured to allow the management team, headed by major shareholder Scott Didier, to retain an interest in the business.

Capervan sale and rental business Tourism Holdings (THL) is also the subject of a private equity bid, this time by BGH Capital. The Trouchet brothers, who had merged Apollo Tourism and Leisure into Tourism Holdings three years ago and are 12% shareholders, are backing the bid. THL has been driving over plenty of potholes. Most recently, geopolitical tensions caused a reduction in US inbound travel and another downgrade in earnings expectations. The price here has thankfully been disclosed, clocking in at a chunky 58% premium to the deeply depressed last traded price.

All three are good examples of how takeover interest can emerge from offshore corporates, local competitors and cashed-up private equity firms. Some major shareholders, especially when they continue to be involved in the business and bemoan a lack of investor appreciation on the ASX, become good partners for acquirers to speak to ahead of any bid.

Businesses in Our Portfolio Worth Watching

They are unlikely to be the last three takeover offers we receive. Several companies in the Forager Australian Shares Fund portfolio are ripe for acquirers, and a few have already seen interest in the past. Here are five we think could appear on dealmakers’ radars in the year ahead.

1. Tyro Payments (TYR)

Tyro operates Australia’s largest non-bank network of payment terminals, servicing over 73,000 merchants in healthcare, hospitality, and retail. The business grew gross profit by 7% in the first half of the 2025 financial year while expenses remained well under control. Earnings were 21% higher and guidance for the year was reaffirmed. The business is on solid footing once again and valuations are attractive.

The Australian Financial Review recently reported that private payments provider Stripe was taking a look at Tyro, and it's not hard to see why. Tyro would give the international payments business instant scale in Australia and a powerful distribution network for Stripe’s online payments products. This wouldn’t be the first time Tyro has been in the crosshairs of acquirers. In late 2022 private equity player Potentia and Westpac (WBC) were working to acquire the business. At the time Potentia bid $1.60, an almost 80% premium to where Tyro stock trades now. With the departure of Tyro’s CEO over the next few months, the door is ajar for an acquirer.

2. ReadyTech (RDY)

ReadyTech is a vertical software business serving education, workforce, and government clients. It generates strong recurring revenue but has seen a moderation in growth recently. What was expected to be a revenue growth percentage in the “mid-teens” is now more like “high single digits”. The share price is off 30% from recent highs.

But the business continues to grow and should improve margins next year. Clients rarely turn the product off, with churn at only 4%. And there is scope for growth to either accelerate or for costs to be cut.

Potential acquirers would be well versed in what can be done. The business was subject to a takeover approach from Pacific Equity Partners in 2022, with the current share price at about half of the bid price. Existing 32% shareholder Pemba Capital has been invested for years longer than one would have expected. While supportive, it’s not unreasonable to think they might be open to an exit at the right price.

3. RPMGlobal (RUL)

A home-grown global software leader, RPMGlobal develops enterprise software for the mining industry. It was the Fund’s largest investment for a long time, and the business has continued to grow. The valuable and low-churn subscription software revenue stream was up 22% in the last half-yearly result.

Unlike some of the other candidates on this list, RPMGlobal is trading close to all-time highs. But it is a strategic asset that has been managed with one eye on sale for many years.

Selling its advisory division at a healthy price has left the business with a clean, sticky, recurring revenue stream which could be attractive to industry players and private equity buyers alike. Plainly disclosing remaining corporate costs mean synergies for potential acquirers are clear.

A competitor, Micromine, was acquired at ten times revenue recently by engineering behemoth Weir (LON:WEIR). This valuation would imply a very healthy premium for RPM Global. The vast majority of the company’s competitors have changed hands over the last few years. RPM could be next on the radar of acquirers.

4. Praemium (PPS)

Investment platform player Praemium has a strong position in the high net worth and separately managed accounts platform niche. It received a bid from competitor Netwealth (NWL) in 2021, which was ultimately rejected. Nearly four years later Praemium is trading at about half of the deal’s implied value at the time. Since then, the logic for platform consolidation hasn’t weakened.